Why Karachi’s Indigenous Coastal Cuisine Finds Itself on the Margins

Why don't Karachiites eat seafood, and other myths.

FOODCULTURELONGFORMWRITINGKARACHI

10/18/202313 min read

An abridged version of this article was first published for New Lines Magazine

A decade ago, in a conversation about cricket, veteran Pakistani journalist Imran Aslam made an off-hand remark about the city of Karachi. “[It is] a city by the sea [which] has no sea culture, because the entire population here is either ‘Ganga Jamni’[from the Gangetic plains of northern India] or from the mountains… nobody really eats seafood, and you don’t see any sailors.” This observation stayed with me for years, and I wondered where the sea was in Karachi’s culture?

Karachi’s popular culture has been centered around its food, which carries an incredible fusion of local flavors from across the subcontinent, as it hosts a diverse range of ethnicities, languages and cultures wider than any other part of Pakistan. Its street food culture serves as a history of migration to the city. The inner city still contains the flavors of Karachi’s pre-partition migrant communities – Goans, Parsis and a host of Gujrati speaking communities including Ismailis, Bohris, Memons and many others. Much of the city’s cuisine is dominated by the northern Indian delicacies Partition migrants brought with them. In the last few decades, the city’s large Pashtun population has also made it a hub for some of the best “karahi” and “chapli kebabs” in the world. (Karahi is a popular meat and tomato stir fried stew, kebabs are herbed and fried meat patties.) Along with all this, being Pakistan’s economic capital has meant that there is also a sizable elite in Karachi being catered to by wood fired oven pizzas and French style boulangeries.

The reason Aslam’s observation struck me was because across the city there were only a few places serving seafood, and most of these tended to be cooked in foreign styles. Forgotten, abused, and ignored, why was the sea absent from Karachi’s culture?

Ecologically, Karachi has treated its sea as a site for waste disposal. Many of the city’s pre-Partition sites where citizens would bathe in, sit by or fish in the sea, such as Native Jetty, are now polluted beyond use. The military – which operates the city’s swankiest housing society – has aggressively “reclaimed” the sea by expanding the Defence Housing Authority (DHA), popular among the country’s richest. In doing so, it has also choked off Karachi’s natural stormwater drainage, leaving the posh neighborhood chaotically flooded each time it rains heavily. Meanwhile, the Clifton beach next to DHA is not only dumped with raw sewage, but the military has consistently blocked access to it for the public, despite the fact that this is the only accessible beach for the majority of the city.

***

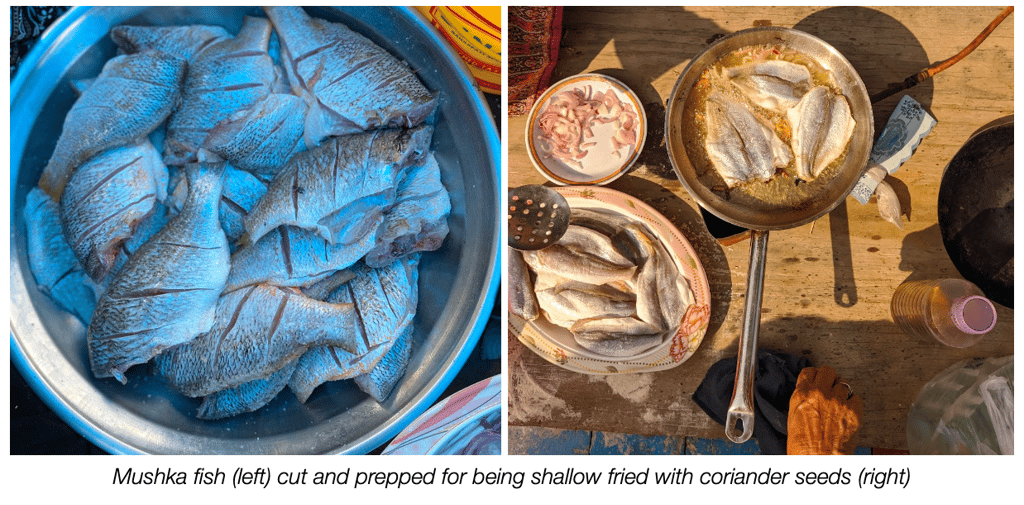

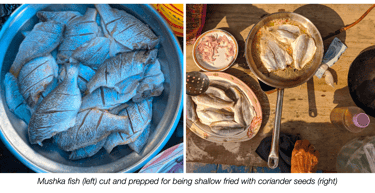

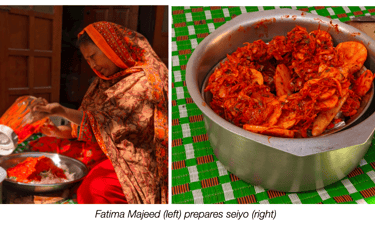

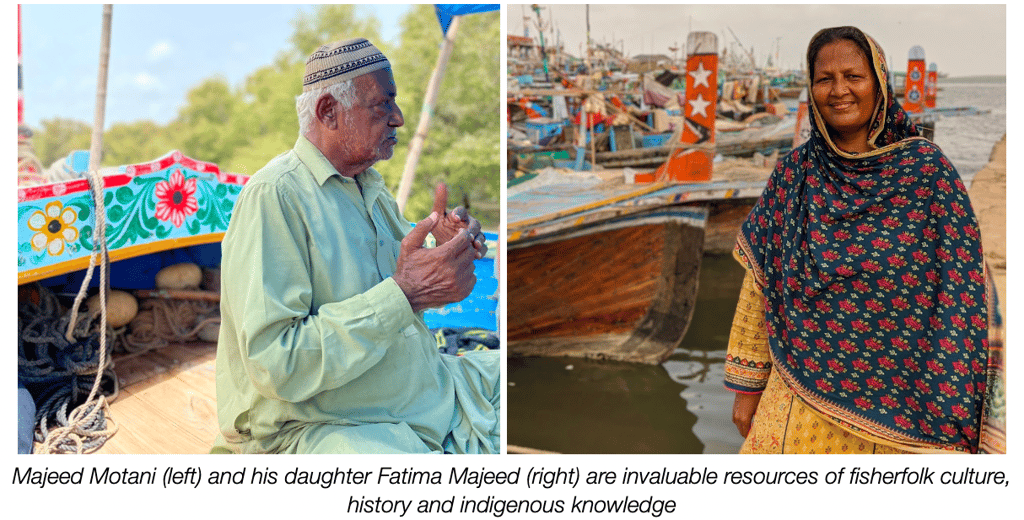

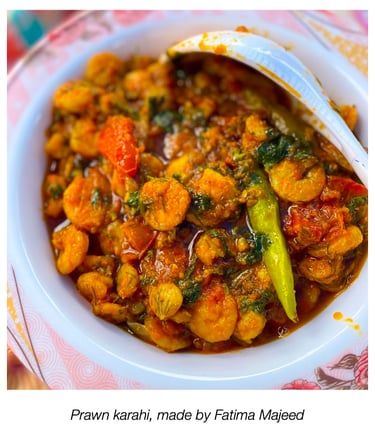

Eventually this past January, the search for an answer led me to the fishing village of Ibrahim Hyderi off the coast of Karachi on an idyllic Friday afternoon. Fatima Majeed, who sat on a charpai – a traditional woven bed used across South Asia – was massaging a fragrant, vermillion paste made of “talhar mirch” (dry red chili), tamarind and garlic onto a pile of sliced onions. The entire concoction was smeared onto thick slices of potatoes and filets of “mushka” (croaker) fish. It was then layered around a shallow bowl with holes in it, so that all of it could be steamed atop mangrove branches inside a large cauldron. This was a dish called “seiyo,” a much loved delicacy amongst Fatima’s family and her community of fisherfolk, the original inhabitants of Karachi.

But in Karachi, the cultural and culinary capital of Pakistan, there isn’t a single place, amongst its innumerable restaurants, cafes and dhabas, that serves “seiyo,” or any of the coastal cuisine native to the region, which speaks to the larger economic and social disenfranchisement of the community. Despite the city’s massive street food culture, Karachi’s indigenous fisherfolk cuisine can only be had at the homes of people from the community. There isn’t a single eatery offering the community’s food.

“There are so many TV channels these days, but I can guarantee you that none of them have ever showcased the traditional and ancient ways with which us mahigeer (fisherfolk) make our food,” said Fatima, a woman who wears many hats in her daily life. When asked to introduce herself, she replied with a smile if I wanted a social introduction or a political one. A lifelong activist with the Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum (PFF), she has been a tireless campaigner for the rights of her people, while also working to secure social benefits and economic opportunities for the fisherfolk community. All along, she and her father Majeed Motani have also kept archives of the ways and culture of their people, as well as the wisdom of living in harmony with the ocean, the mangroves and all the creatures within them.

The fisherfolk community is part of the Sindhi and Balochi speaking communities, which are the original inhabitants on the coastlines of Karachi, as well as along the banks of the Indus river’s tributaries flowing out to the Arabian sea. However, with the influx of mass migration through Karachi’s history, these communities have found themselves increasingly marginalized on their own ancestral land. When I asked Fatima why Karachi’s original inhabitants were so definitively absent from the city’s cultural and culinary scene, she said that they had been “deliberately kept back,” be it their food, culture or economic and social opportunities.

When I asked Zahra Malkani, an artist whose practice engages with indigenous histories and ecological knowledge in the city, she said that the erasure of indigenous communities from Karachi’s popular culture has to do with the nature of different migrations into the city, and how the city was organized around those waves of migration.

The historical record for a port in the area of present-day Karachi arguably goes back to the time of Alexander the Great’s foray in the region. But it was in the 18th century when businessmen from Sindh, led by Seth Bhojo Mal, established a major port and fortress in the city. It led to the arrival of migrants over the ocean, which included people from areas in present-day India, such as Gujarat, the Konkan coast and Kerala in the east, as well as inhabitants of Oman, the Persian Gulf and the Horn of Africa in the west.

In 1947, when India and Pakistan were created, this oceanic link was overwhelmed by land-based migrations. At first, millions of Partition refugees – Muslim families from north and central India escaping communal riots – flooded the city and changed its demographics overnight. From being a Hindu majority city in 1941 with only 42% Muslims, Karachi became 96% Muslim in 1951. Similarly, from being a majority Sindhi speaking city, a decade later native Sindhi speakers comprised only 8% of the population, while 51% were Urdu speakers, the language spoken by Partition migrants, and the national language of Pakistan. Over the years, this was also compounded by economic migrants from southern Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces, and later war refugees from across Afghanistan and western Pakistan.

Another way the fisherfolk were marginalized was through the city’s post-1947 housing societies and infrastructure projects. Take the area of Korangi, which was developed by the military government and celebrated as being based on modern, urban reconstruction efforts inspired by post-war Europe. But the land was acquired using the draconian, colonial-era Land Acquisition Act of 1894, and indigenous communities who had lived there for millennia were driven off forcibly.

This continues to this day, as evidenced by the brazen scandals surrounding Bahria Town, an elite-housing society made by Pakistan’s richest man, Malik Riaz. The land was coercively purchased from indigenous communities, who had alleged that police interference and violence was used to force the sales. In a move that shocked many, the Supreme Court later accepted a proposal by Bahria Town to pay a fine instead of returning the land as the court had initially ordered.

“If you look at the history of Karachi, you will see that the city was made by the mahigeer. This was a fishing village which was named after a fisherwoman Mai Kolachi,” said Fatima, referring to the legendary fisherwoman recalled in various folktales and songs. Despite being named after a fisherwoman, this city has seemingly forsaken its fisherfolk, said Fatima. “[Over time] we have seen that the cultural presence of the mahigeer has been imprisoned.”

To convey what she meant by imprisonment, Fatima gave the example of Moriro, who is spoken in some accounts as Mai Kolachi’s son, and legendary for slaying a sea monster that had killed his six brothers. Today, many fisherfolk name their children after him, and he remains a central figure in their imagination. There are at least two grave sites in the city where he is believed to be buried, but people cannot visit one of them, since the Pakistan Air Force base Masroor was constructed around it, and the heritage site, which was visited by locals for generations, became off-limits for them.

Similarly, the military barred access to traditional fishing sites, such as those close to DHA or near the new Lucky Coal power plant. Fisherfolk often come under gunfire, face arrests and destruction of their boats when they try to access the sea near these areas, said Fatima. Hence, many have now internalized the fear of the authorities.

This sense of top-down, elite-centered governance can also traced back again to the Partition-era migration, when Muslim families from India – the main base of the All India Muslim League, the political party that had led to the creation of Pakistan – viewed themselves as the architects of the country’s future and led to the development of a very centralized state that privileged the concerns of this migrating elite.

This form of governance is palpable when one considers Karachi’s beaches. Except the heavily policed and regulated Clifton Beach, all other beaches are far away from the city center, accessed by permanently damaged roads, and absolutely bereft of any local seafood or even coastal culture in the form of music etc. The most popular French Beach in Karachi has been physically walled off, with only those owning fabulously expensive huts within it allowed entry. Consequently, for many Karachiites, ignorant of their city’s oceanic character, there is a common complaint that the city lacks a “beach culture,” by which they mean what one sees in the West with surfers and swimsuits and deck chairs with cocktails.

“[But] I think that Karachi actually does have an incredibly rich and vibrant beach culture, which is full of incredible food and folklore and music, and really, really beautiful entanglements with the sea,” said Malkani.

***

Like many South Asian cuisines, many dishes of the mahigeer begin with bases made with masalas, or spices, from which more elaborate dishes emerge. There is a green paste, made from mint, coriander, tamarind and onions. The red paste is made with fragrant, colorful yet mild talhar mirch, as well as garlic and tamarind. They can be used in various ways, such as chutneys atop crisp filets, as a marinade or for curries. They can also be part of a pulao (rice dish) preparation. The general taste profile of these dishes is more sour and herby, rather than spicy, which is common across Karachi.

“Biryani made from prawns is very delicious. We also make meatballs from prawns, prawn mincemeat, curries made from prawns, kebabs made from prawns,” explained Fatima. To make kebabs made of prawns – locally called “chilla” – prawns are peeled and ground in a paste on a “silbatta” (grinding stone). Onions and dill are added with coriander, spices and salt, along with tamarind pulp. They are then given shape using tamarind water and fried in oil. “Whenever someone would make these, a beautiful fragrance would envelop the whole neighborhood, and then all their friends and relatives would show up asking for a taste,” she said.

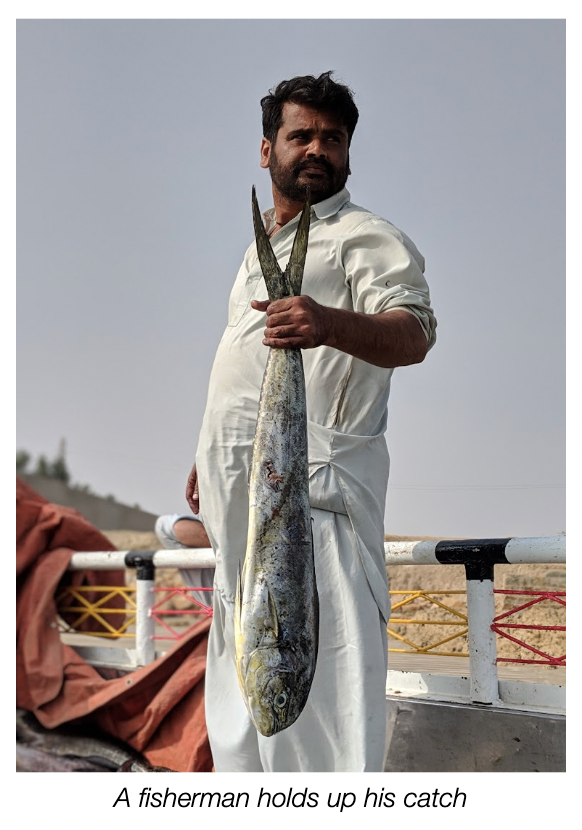

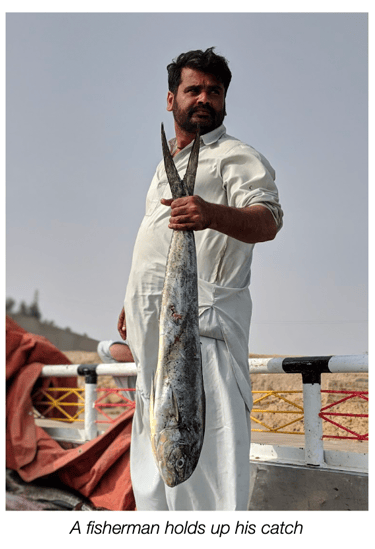

There are a number of fish that are found around Karachi, such as black barracuda, bhekti, white and black pomfret, sharks called mangra, croaker, white sardine, flathead, red snapper, Indian salmon, queen and king fish, lemon sole and red snapper, with each associated with different types of preparation.

A delicate dish like dohtar(javelin grunter) is used in a “seiyo” or “baphu.” Baphu is a clear tangy soup made with vegetable broth, tamarind seeds and garlic; seiyo, as explained above, was a steamed dish made with chilis and potatoes. For pulao or a curry, a fish like aal (queen fish, also locally known as “saram”), which has a very sweet taste, is preferred. To fry, mushka or paaplait(pomfret) fish is used. The mahigeer also use a lot of dried fish. Smaller dried fish are often toasted and eaten for breakfast, and dried lemons are a staple in several curries made with dried fish.

One of the most striking features of the cuisine is that other than potatoes, almost every ingredient used in these recipes is native to the region, or is available via ancient oceanic trade networks. These range from herbs like coriander and fenugreek, to tamarind and talhar chillies, to spices such as black pepper, cinnamon and nutmeg.

But what is unique is that the fisherfolk use spices for non-edible purposes too, particularly as decorations and garlands during weddings. “Whichever house has a bride sitting for her ‘maiyuun’ (a pre-wedding ritual common in South Asia), the whole neighborhood can smell the scent of ‘jarri bootiyan’ (herbages) from there.” Garlands are also made of the whole seeds of different spices for the bride.

Similarly, many social traditions in the region celebrate seafaring life. For instance, When a new boat is about to make its maiden voyage, relatives and well-wishers garland the owner with flowers. They tie “ajraks” (clothes adorned with a block-printing style traced back to the Indus Valley civilization, central to Sindhi heritage) and colorful dupattas (traditional shawl-like scarfs) to the boat, and distribute dates amongst each other. The boats and launches are also elaborately decorated for Eid. During Ramadan, fisherfolk mosques would raise flags which were taken down when it was time to open the fast, after which large communal feasts would be served.

***

While there were no exact figures available, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence from older Karachiites that up until at least the 1980s, local seafood was found as regularly in Karachi’s markets as poultry and red meat. But today few bazaars and markets offer any form of seafood, and those that do often have imported produce instead of local. Moreover, once Karachi’s produce started being exported to places such as Dubai, Kuwait on a daily basis – and later Singapore, China and Japan – the only seafood in the local markets was the stuff that was unsold and of a much lower quality.

Perhaps in the most ignominious irony, that the greatest demand in the city was for making “finger fish”, breaded fried fish served often at weddings, said Hussain Rupsi, whose family has been running a fish exporting business for several decades. But instead of using local produce, Hussain claimed such dishes were all made from fish imported from Vietnam, which was cheap and of such poor quality that it had been rejected by other markets. Even from the rejected, low quality seafood, as much as 65% is sold to Punjab province, estimated Rupsi, where there has been a long standing culture of eating fried fish in the winters.

These vast and profound changes in the economy of the sea have had a crushing impact on the fisherfolk, whose political and social exclusion was exacerbated by their economic marginalization. As the fishing industry expanded, capital poured in from around the country but the fisherfolk were reduced to the lowest-paying, labor-intensive jobs.

“We often say that the earnings from the ocean rarely go into our pockets,” said Fatima. “We had always seen fishing as ‘rozgaar,’ a means of making a living. But when it became an industry, we were very rapidly marginalized, as we lacked the capital and opportunity to establish and purchase factories, stores and large mechanized launches ourselves. We were restricted to just catching the fish, but not making the huge profits made off our catch.”Most of them were already operating at a smaller scale with little access to capital, and as industrialization increased, they lacked the economic ability to compete, as the factories along the port and jetties, and the larger fishing launches and ships, were owned by immigrant populations.

This economic marginalization comes hand in hand with ecological devastation as well. Fisherfolk have long complained about the ravenous, industrial trawlers operated by Chinese companies that wipe out much of the catch. There is unregulated use of illegal nets, which kill out even the tiniest baby fish, leading to drastic falls in the population of various species. Moreover, Karachi’s vast, untreated sewage also dumps into the ocean.

With fisherfolk unable to fish in their usual areas and finding local marinelife populations dwindling, many have been reluctantly forced to fish during the off-season as well, when many of the species are breeding. “No real mahigeer would ever want to go fish during June-July (the breeding season) because we want the sea to be able to rest and for prawns and fish to have the time to replenish their populations,” said Fatima. But with the economy in doldrums and most struggling to survive, many fisherfolk are left with no choice but to participate in harmful practices.

The situation has gotten to a point where the very communities that have been defined by their relationship to the ocean have become increasingly decoupled from them. In previous years, the hired labor that went on fishing expeditions would be able to take home a large share of fish when they returned. But now, with prices rising and fish populations plummeting, the boat owners end up selling everything, and fewer fisherfolk are actually able to regularly eat fish at home. As a result, local consumption of seafood has drastically reduced.

In one sense, I felt I had the answer to the question Aslam had provoked in me all those years ago. It is not like Karachi doesn’t have a sea culture, but rather that a millennia old legacy of ecological wisdom, lived intimacy and symbiotic existence with the ocean that Karachi’s original inhabitants have developed has been systematically erased, devastated and marginalized.

With climate change and late stage capitalism in full gear, it feels like it might already be too late to reverse that. But yet, such defeatism ignores the fact that the traditions and culture of the mahigeer have existed long before anyone else arrived in Karachi, and despite the past seven decades or so, Karachi has always been a city by the sea. The question isn’t whether the ways of the mahigeer can be saved, but rather if the people of Karachi can learn how to truly embrace the ocean that surrounds them.

Boat illustration at top and this by Hafsa Ashfaque