The I Who Becomes A We - the importance of forgetting to fandom

An essay for the Indus Valley School's Hybrid, an interdisciplinary journal of art, design & architecture, on why forgetting is essential to being a sports fan.

CULTURELONGFORMWRITINGPOLITICS

6/22/202417 min read

The advertisement cuts straight to the heart - a Pakistan fan takes out a box of fireworks every four years intending to celebrate a win over India at the cricket world cup - a moment that never comes as the fan ages over twenty-three winless years.

Played on Star Sports for the 2015 World Cup, when Pakistan suffered their sixth consecutive World Cup defeat to India, the ad went massively viral, to the point where even Pakistan’s star player Shahid Afridi referenced its catchy song - Mauqa mauqa* - a reference to the long-suffering fan's neverending desire for one mauqa to celebrate an Indian defeat.

*Mauqa literally means a chance or opportunity. The refrain in the song’s ghazal speaks of the yearning for this one chance of savouring a victory over the arch-rivals.

There is a famous cliche in British football which goes “it’s the hope that kills you.” The idea being that while it is painful to watch your favourite team lose, what hurts far more is when you have hope that they might come through. Rather than resigning to certainty, you hope that this time might be different, which makes the eventual disappointment feel worse. The everyman in the Star Sports ad depicted several decades of a life millions of Pakistani fans had lived through, hoping for victory against their arch-rivals at the biggest stage. And like him, many of those fans had sat for each consecutive defeat with the hope that this time, things might be different.

I have spent the last few years thinking about why we watch sports, a topic that I have written on when I was a younger, more naive writer. A big reason for this was that after several years of working as a journalist and consultant in cricket, I found that I had lost my ability to enjoy the sport as a fan. I began to wonder what was at the core of the experience of being a fan in the hopes of diagnosing my own malaise.

For a long time, I believed that we watch sports because it’s fun to take part in the glory that comes with victory, but when supporting a team as fickle as the Pakistan’s men’s cricket team, glory is the rarest of treasures. Far more common is absolute catastrophe, ranging from criminal scandals to jailed stars; terrorist attacks to senate hearings; doping to fixing; and an infernal habit of miraculously finding new, often hilariously tragic ways to lose. Why did any of us come back each time to watch this team?

The penny dropped for me a few years ago, when I saw the title of a sports documentary called Maybe Next Year (2021)*. The phrase, maybe next year, is uttered by every losing fan once their team falls out of contention - and given that only one team can win an event, it's a phrase used by the majority of fans. ‘Maybe next year’ is the hope that maybe next year, next season, next time would be different, would give joy instead of sorrow. The more I thought about it, the more these three words seemed to betray the essence of sports fandom - the ability to forget the past, to forget the pain and the agony, to forget, for example, the taunting advertisements made by an economically dominant and rapidly fascist neighbouring country; the ability to forget all of that and somehow return to watch the team once more with the hope that this time, it might work out.

*The film covers the notorious fanbase of the Philadelphia Eagles, an American football team. Their fans were renowned for their rowdiness, their vitriol and their unstinting support for a team that had not won a title in almost six decades. In a most serendipitous twist however, the year that the film was made ended up being the year that the Eagles won their first ever Super Bowl, the sport’s highest prize

In other words, ‘maybe next year’ or the dream of the mauqa, represents the moment when sports fans forget all that came before, and renew their hopes for the future. While sports can give rise to many forms of forgetting, it is this forgetting that is at the heart of being a fan.

Sidetalk is a popular social media channel that posts short videos chronicling the streets of New York. In 2021, one video documenting the fans of the local basketball team after they had won a game broke the internet. The maniacal, unbridled emotions of the fans felt extremely universal. One person in the video, speaking with raw emotion, asserted into the camera that “‘We had De Blasio, we had Cuomo, it was rough shit. But we have the Knicks.” Later, a top-rated comment on the video repeated that line, and noted “that's actually kind of beautiful when you think about it.”

For context, Bill De Blasio and Mario Cuomo were a former mayor and governor of New York who were largely despised. The prevailing sentiment was that supporting the local New York Knicks team allowed fans to get through the tough times under those political leaders. It showcased one of the best things about sports’ ability to forget, and I found myself watching the video many times since it came out.

It took a while for me to realise something I found very funny.

For the entirety of De Blasio’s time in office and the majority of Cuomo’s, the Knicks were statistically one of the worst teams in their league. Moreover, the Knicks have always been one of the worst teams in their league, having last won a title fifty years ago, and having generally been terrible ever since. And perhaps best of all, the fans were celebrating a win in the opening game of an eighty-two game season. In other words, they were losing their minds, they were baring their souls and sharing their hopes and fears on camera over what amounted to success in just the first step of many, many more. (Spoiler Alert: The Knicks did not win the title that season.)

I kept thinking about that guy from the video - how exactly was supporting the worst team in a sport helping you deal with “rough shit”?

This paradox - how being fans of a tragicomic team could somehow be soothing for people suffering real life problems - was something I had begun to wonder about with my own fandom of the Pakistan cricket team.

Over the last few years, every time the Pakistan cricket team manages to lose a match in a gut-wrenching way, people online resurface an old tweet of mine. It goes “When I have kids I'll get them hooked to coke and heroin at a young age so they never get involved in an addiction as fkd up as Pak cricket.” At the time, I felt an addiction was the only way to describe my fandom for the team. One reason that I perhaps saw this as an addiction was that around once a decade, Pakistan would win a major title and as I understood it, that allowed me to sign up for a decade more of hurt.

But this Knicks video shattered that premise - here were fans who had spent multiple generations without any major titles and accolades, and yet they were expressing the same emotions as any other fans. This was the video that convinced me that fans were not supporting their teams for glory. Fans like those of the Knicks proved that they weren’t even expecting a bare level of competence in return for their obsession. Instead, they were fans because sports fandom allowed them to forget all the rational evidence about their team, all the memories of its failures, and all the heartbreaks it caused because sports offered a truly immersive, communal, almost sacred experience.

The novelist Eduardo Galeano wrote in his seminal work, Soccer in Sun and Shadow, how attending a football match was a secular ritual. “While the pagan mass lasts, the fan is many. Along with thousands of other devotees he shares the certainty that we are the best, that all referees are crooked, that all our adversaries cheat… Rarely does the fan say, “My club plays today.” He says, “We play today… And then the sun goes down and so does the fan...The stadium is left alone and the fan too returns to his solitude: to the I who had been we.”*

*Galeano, Soccer in Sun and Shadow. 24

By writing the ‘I who has been we’, Galeano describes the universal journey of every fan, as well as alluding to that sense of community that fandom provides. And while this sense of community exists most powerfully inside a stadium during a match, it also exists across time and space, connecting fans across continents and generations and lifetimes in a shared communal experience.

Ultimately, fans forget so that they can participate in this secular ritual once more. So they can participate in that feeling of having something out of their control, like the outcome of a cricket match, feel so meaningful. They wish to relive that feeling of community, where the entire fandom pulls as one in feeling hope, in feeling joy, in feeling sadness and despair, in feeling all those feelings deeply and together.

In the aftermath of the epic men’s World Cup final in 2022 between Argentina and France, the writer Zito Madu called out the simplistic impulse to view the results solely about winners and losers. He wrote that “it seems to me that it would be better if athletes were judged as artists as well, so that we can see their great performances and seasons as the masterpieces that they are. Performances that we should sometimes stand in front of, without debating and trying to tear each down in comparison to another, and simply enjoy.”* It was a beautiful and elegant approach to sport’s obsession with binary narratives of defeat and victory.

*Madu, “The World Cup Belongs to Lionel Messi.”

But the more I thought about this radical proposal, the more I felt that it might not be radical at all. That while fans might not view athletes as artists, they certainly do move past who wins and loses. When a new season of sports comes around, it is not just fans of the previous champions, but also fans of every other team who renew their hopes for victory. It appears that when speaking about fandom in general, it is the continuity, the resetting and renewal that keeps them hooked, keeps them returning even when their team is terrible.

Fans forget so that they can become fans again and again. They forget so that the “I who was” becomes a “we” once more, even for a brief while.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bibliography

Dash, Mike. “Blue versus Green: Rocking the Byzantine Empire.” Smithsonian Magazine. Published March 2, 2012. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/blue-versus-green-rocking-the-byzantine-empire-113325928/.

Farah, Yoosof. “World Football’s Defining Moment: Iraq Rise from Guns to Glory.” Bleacher Report. Published April 22, 2010. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/382188-world-footballs-defining-moment-iraq-rise-from-guns-to-glory.

Learn English through Football, “Football Cliche: It’s the Hope That Kills You.” Podcast 1:15. May 15, 2012. https://languagecaster.com/football-cliche-its-the-hope-that-kills-you/#:~:text=Listen%20here%3A%20It%27s%20the%20hope.

Galeano, Eduardo. Soccer in Sun and Shadow. London New York: Verso, 1998.

Gemmell, Jon. “Bradman’s Cultural Legacy.” Bleacher Report. Published August 26, 2008. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/51090-bradmans-cultural-legacy.

Goldenberg, Suzanne. “Footballers Who Paid the Penalty for Failure.” Published The Guardian, April 19, 2003 http://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/apr/19/iraq.football.

“Hansard - ACT Legislative Assembly.” 2001. Webcache.googleusercontent.com. February 28, 2001. https://www.hansard.act.gov.au/hansard/4th-assembly/2001/HTML/week02/351.htm

Madu, Zito. “The World Cup Belongs to Lionel Messi.” ESPN. Published January 10, 2023. https://www.espn.in/football/story/_/id/37634966/the-world-cup-belongs-lionel-messi.

Phillips, Brian. “College Football’s Schism Moves Us Further Apart than We Already Are.” The Ringer. Published August 11, 2020. https://www.theringer.com/2020/8/11/21364177/big-ten-pac-12-college-football-postponed-coronavirus.

SidetalkNYC. “Knicks Season Opener - Sidetalk.” YouTube video 0:56. . October 21, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mkhrUM35CQo.

Wilson, Jonathan. Angels with Dirty Faces: The Football History of Argentina. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2017.

Originally published in Hybrid 06. Click for the original article in PDF

It should have been the pinnacle of Cesar Louis Menotti’s career, The long-haired, flamboyantly besuited manager of Argentina’s football team was more of a philosopher whose vision of an idealistic, purposefully romanticised attacking style of play had led his country to its first ever World Cup win. It was expressly referred to as a joyous, ‘left-wing’ style that stood in contrast to the previous decades of more defensive, violent football played by Argentina.

But the reason for Menotti’s ambivalence was that “[o]n the pitch, Argentina’s leader General Jorge Videla, grinning beneath his moustache, oiled hair gleaming in the floodlights, presented the World Cup trophy to …Argentina’s captain. As [he] raised it to a roar of celebratory patriotism, Videla turned to one side and raised both his thumbs in glee.”* For all of Menotti’s on-field politics and style, the cold hard facts were that the World Cup win was an invaluable, peerless PR win for General Videla’s ruthless junta which had ruled Argentina since 1976. The junta was most notorious for their brutal ‘dirty war’, which referred to the deaths of at least 30,000 people, many of whom had disappeared for years. Even during the leadup to the World Cup and the event itself, protestors had thronged the major cities, but as the team kept winning, their glory drowned out all other noise.

*Wilson, Angels with Dirty Faces, 388.

In his history of Argentine football, Jonathan Wilson quotes the anthropologist Eduardo Archetti, who tells stories of ”prisoners shouting, ‘We won! We won!’ in their cells and being joined in their celebrations by Captain Jorge Acosta, ‘el Tigre’, one of the most notorious of the torturers. He then took some of the prisoners out in his car to witness the delight on the streets, so they could see that the people as a whole didn’t care about the protests.”* Wilson also quotes Claudio Tamburrini, a lower league goalkeeper and a philosophy student imprisoned by the regime who says that “to support the national side of a country that is subjected to a dictatorship is an example of a costly irrationality.”

*In a remarkable twist, Argentina’s second World Cup win came in 1986, four years after the junta’s disastrous military defeat to the British over the Falkland Islands led to the end of the right-wing dictatorship. Carlos Bilardo, Argentina’s manager in 1986, and his team meanwhile were the right-wing antithesis to Menotti’s side, and for decades Argentina’s copious football discourse was defined by a split between menottisme and bilardisme.

Yet sport’s capacity for provoking this ‘costly irrationality’, this forgetting of oppression, has long been one of its most desirable aspects for oppressors everywhere. The topic of ‘sportswashing’ is currently trendy as Saudi Arabia has launched an impossibly wealthy attempt to own or acquire sporting teams and institutions. Saudi’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) is currently about to control international golf with its alliance with the Professional Golfers’ Association (PGA) Tour. In addition, it also purchased the English football club Newcastle United, and over the last year has attracted many of European football’s top players to its own domestic league using eye-watering sums of money. Their actions themselves are a belated response to the UAE and Qatar’s far longer use of sportswashing*, as both states had essentially purchased (through intermediaries) the football clubs Manchester City in England and Paris Saint Germain in France.

*There is a veritable cottage industry of people from the global South calling out the hypocrisy of the global North protesting Qatar’s considerable ethical and criminal crimes as it hosted the football World Cup, but my favourite example is that literally the very previous edition, which raised very few moral concerns, was held in Russia, a few years after its annexation of Crimea, a few years before its invasion of Ukraine.

But this is not to imply that sportswashing is a contemporary phenomenon brought about by petro-states looking to make their name on the world stage. BothEven Argentina itself, as well as Australia, provide great examples of the scale and durability of sport’s ability to make us forget social sins. Both these countries became modern nation-states that catered to their dominant population of settler-colonialists from Europe. Both of these countries had also largely wiped out and suppressed their native populations through war and genocide. In the early decades after their creation, these countries struggled to find an identity for their condition of being racially and culturally proximate, yet geographically distant, from Europe. In both cases, it was sport that helped shape the national identity.

While football is followed passionately in many parts of the world, Wilson’s work shines a light on a century-old history of Argentine obsession with the game, as novelists, artists, filmmakers and other intellectuals depicted their national identity through the prism of football. One of the most famous examples of these was the football editor Borocotó. In 1948, he co-scripted what is considered the essential film of Argentine football called Pelota de trapo (Ball of Rags) which tells the story of a street urchin, called Comeuñas, who learns to play with a ball of rags on a dirt field in the slums. He rises to become a top-class player, but in a key match before archrivals Brazil, doctors tell him he has a chronic heart disease and could die if he played. “At the moment of crisis, Comeuñas gazes at the Argentinian flag and resolves to play: ‘There are many ways to give your life for your country,’ he says, ‘and this is one of them.’ He pulls on the (Argentine jersey) and scores the winner. Although Comeuñas’s chest pains continue, he lives to the end of the film.”*

*Wilson, Angels with Dirty Faces, 202.

But perhaps more magical was Borocotó’s article in 1928, where he described the idea of the ‘pibe’, an idealised figure of a diminutive street-urchin who possesses both fantastic footballing skill and considerable cunning, having learnt the game on the streets. The full text is remarkable to read because it ends up being a strikingly accurate description of the Argentine great Diego Maradona, who would arrive about fifty years later and become arguably the greatest football player of all time.

An excellent example of this is in the unbelievable story of Iraq’s triumph at the 2007 Asian Cup in football. Iraq was historically a powerhouse of Asian football, but it suffered a great decline during the height of Saddam Hussain’s reign. The worst of it was called ‘The Dark Era’, as Uday Hussain - Saddam’s notorious son - took control of the football federation and “tortured players who played poorly, punishing them by sending them to prison, making them bathe in raw sewage and kick concrete balls, and shaving their heads among many other punishments.”* Uday succeeded in decimating much of Iraqi football’s previous success.

*Goldenberg “Footballers Who Paid the Penalty for Failure.”

By 2007, Saddam and his sons were long gone and replaced by a deadly civil war in the aftermath of the American invasion. All of Iraqi society was in disarray, which is why the team’s unexpected success at the tournament became a huge rallying point for society. Indeed, despite multiple horrifying suicide attacks on celebrating fans, the streets continued to be full of joyous fans after every win. As one fan said after the victory in the final, “it was not a football match; it was Iraq's one chance to show the world who they truly are.”* It is hard to find anything that can help a society forget unending levels of violence and despair, but this is where sport’s power to forget can also be a useful thing.

*Farah, “World Football’s Defining Moment: Iraq Rise from Guns to Glory.”

But talking about a war-torn country winning a major tournament is taking things to an extreme. It might end up suggesting that sports fulfils this function of forgetting only when glory is achieved, but the reality is that even the most mundane and modest of teams can provide a lot of joy by simply existing. And that goes to the heart of sports-related forgetting that I find myself most interested in.

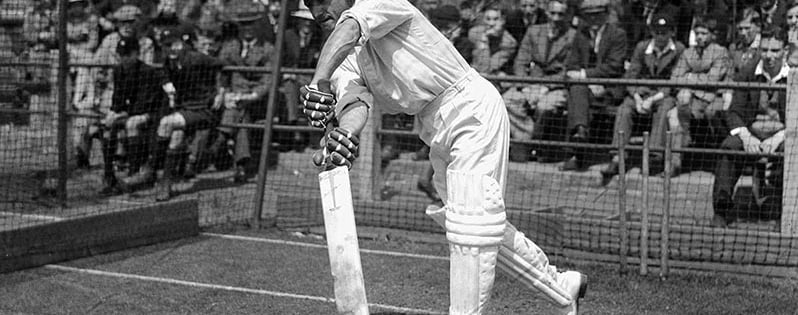

Similarly, in Australia, sport had a tremendous impact on shaping the national psyche of the colonial settler population. For them the sport in question was cricket, and in particular the otherworldly success of Donald Bradman*, who as one author described, “enjoys a status in Australia that other countries bestow on those who lead revolutions, create immortal works of art or make great scientific breakthroughs.”**

*Bradman’s greatest successes came against the English during the peak of their colonial might, and one result was that outside of his home country, the greatest volume of his fan-mail arrived from pre-partition India.

**Gemmell, “Bradman’s Cultural Legacy.”

Bradman arrived on the scene during the Great Depression and was a precocious talent of incredible promise. Like Maradona for Argentina, Bradman’s combination of homespun technique and attacking instincts came to be seen as a stand-in for a larger national identity for the settler-colonial population of Australia. For example, one politician said that Bradman’s “training technique of hitting a golf ball against a rainwater tank with a cricket stump is part of Australian folklore.”* The reason it is so central to Australian identity is that it serves as a basis of a national mythology, of an idealised sense of what it means to be (a white) Australian. A young boy trains himself using limited resources and becomes the greatest batter ever seen is a story that the nation wants to tell about itself as well.

*“Hansard - ACT Legislative Assembly.”.

In both Australia and Argentina, the settler colonial populations used the mythology of sport to create an identity which didn’t need to contend with the violence of their presence on that land - an identity which allowed them to forget their original sin, and create a new one where they are the righteous heroes who overcame great odds.

In fact, beyond providing the basis of a national identity, some have argued that sports also does the job of bringing the imagined nation into life. If we turn our attention to another settler-colonial state - the USA - we find the writer Brian Phillips making such an argument. Americans play their own version of football (called American football) and while the professional league is the richest in the world, the far more popular version of the sport is played at the college level. When the Covid-19 pandemic caused widespread changes to the already complicated college football season, Phillips wrote about the impact that the sport’s timetable had on society:

“…all timetables, [are] a window into the civilization that created [them]. What it makes me think about, mainly, is how much hard work goes into knitting a country together, how the enormous difficulties of physical space and regional difference can only be overcome with great … imaginative labor. A … timetable, then, [is], among other things, a powerful imaginative act. College football exists…somewhere in the … process of cultural adhesion… it’s a game about taking disparate places and turning them into a place. It’s an interface. Every time two teams play, every time fans caravan in from farm country [to watch a game] …every time that happens … a little span of distance is collapsed.”*

*Phillips, “College Football’s Schism Moves Us Further Apart than We Already Are.”

At this point, it might well feel that the primary function of sports is to allow for terrible politics to take place. The types of forgetting described above are all in the service of oppressive political forces. Indeed, for the Roman poet Juvenal, this was precisely the problem with sports. He bemoaned that the Roman public had abdicated its political responsibilities, and instead spent their time yearning for “bread and circuses”, with circuses referring to gladiator bouts and chariot races that autocrats would organise as a way to gain political power. Yet the Roman tradition of chariot racing provides my favourite example of how this power of sports - the power to create new identities or forget old ones - can occasionally become chaotic and uncontrollable.

At a chariot race iIn 532 CE, during a time of considerable economic and social unrest in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, fans of opposingrival teams attending a chariot race suddenly began to chant in unison, despite their fierce rivalries. According to popular historian Mike Dash “[t]ogether, the two [fan] factions shouted the words of encouragement they generally reserved for the charioteers—Nika! Nika! (“Win! Win!”) It became obvious that the victory they anticipated was of the factions over the emperor, and with the races hastily abandoned, the mob poured out into the city and began to burn it down.”

It behoves me to add some context. At this point in the Byzantine empire, fans of chariot races were powerful political and social actors, comparable to similar fan groups in global football today, who sat at the nexus of fandom, politics and criminality. Eventually one fan group betrayed the other which led to mass executions.*

*Dash. “Blue versus Green: Rocking the Byzantine Empire.”

I love thinking about this story, particularly when ghastly political aims overwhelm the naive joys of sports, because it reminds me that there is only so far that the spectacle of sports can be abused by oppressors. And in some extreme cases, sports offers a sense of hope and redemption that few other things in life can offer.