Kaun Talha? The Icon Interview

Talha Anjum breaks down the journey of his career, including how his rapping began, what is his creative vision, and whether beefs are an art or science.

CULTUREMUSICWRITINGLONGFORMKARACHI

Ahmer Naqvi

1/26/20259 min read

A review of Talha Anjum’s short film Kattar Karachi published in Icon (Karachi Without Depth, January 5) had one main question about the film — why?

As in, why is this rapper making a film starring himself, and why would this be notable? In effect, this sentiment dismissed the effort as merely a vanity act which had several flaws. It is an understandable critique if the movie is seen purely as a film, but doing so would also be to miss the point: Kattar Karachi exists because it is the victory lap of the country’s biggest musical superstar at present, and an extension of an unprecedented album launch.

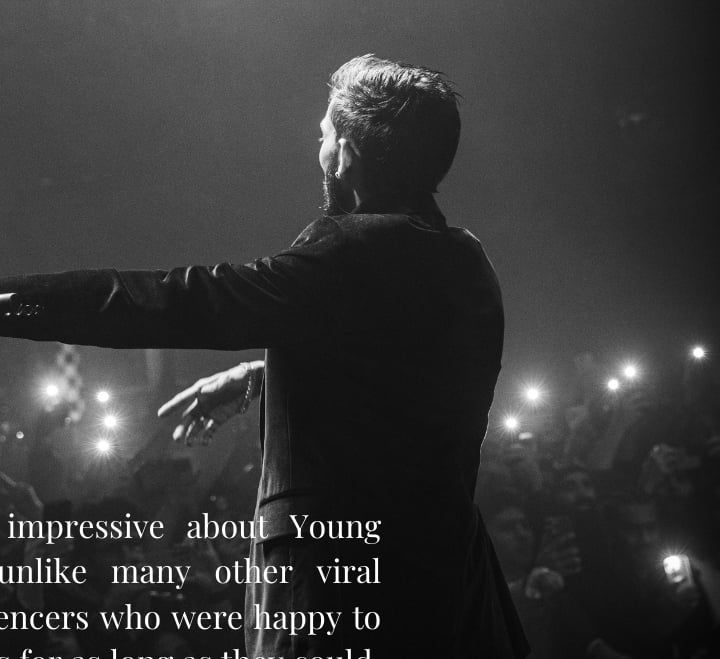

Recently, when Talha Anjum showed up at a local mall to promote Kattar Karachi, the sizeable crowd that had assembled there to see the rapper — who is currently the most streamed and perhaps the most popular artist in the country — almost led to a stampede.

If you’re someone my age or older, there might be a chance you’re not truly sure who Talha Anjum really is (try saying “Kaun Talha?” [Talha who?] out loud in front of young people to find out), so let’s use the crutch of mainstream culture to explain.

Remember the first time you heard about desi hip-hop in Ranveer Singh’s Gully Boy? The rapper whose life the movie was partially inspired by, Naezy, recently provoked a major brouhaha by claiming to not know who Talha Anjum is. One extremely viral diss-track later, Talha had not only made his mark and obliterated any critique, but soon mainstream luminaries such as Badshah (the guy soundtracking all the mehndis you attend this winter) were coming out to proclaim their longstanding admiration for Talha’s work.

In light of all this, Kattar Karachi can be seen as an attempt by a musician who’s scaled quite a few peaks to build one of his own to climb. There were no worlds left for Talha Anjum to conquer, so he had to build new ones with Kattar Karachi.

Cultural critic Hadi Ahmad coined the phrase ‘The Anjum Universe’ to describe the intentional coherence of the characters and stories within multiple music videos released by the artist, with the same stories and characters seemingly carrying over from one video to the next. He argues that, for young audiences who’ve grown up with social media, the standard tropes of music videos have become predictable, and that Talha recognised that “his audience is evolving like crazy, they have understood the [standard music video] format … and they want something more. I think that’s where Kattar Karachi plays a massive role, because it evolves that format.”

If Pakistan were a country with a viable and functioning music ecosystem, Talha would have been on the cover of magazines, headlining the Top 10 countdowns and charts, appearing on music channels, being discussed in print and on blogs, and receiving prestigious and meaningful awards.

But Talha is past whatever little that does exist of a musical ecosystem. He has completed the holy troika of Pakistani music in doing a soft drink campaign, appearing on Coke Studio and doing the league anthem for the Pakistan Super League (PSL). He went further still, being signed by Mass Appeal, the record label run by American rapper and entrepreneur Nas.

And he keeps going, overtaking Atif Aslam as Pakistan’s most streamed artist, who’s been at the top longer than smartphones or social media have existed! Perhaps, most impressively, he crossed the final and most important frontier for Pakistani artists — the Indian market — without leaning on Bollywood releases.

In 2017, a rap producer called Sharaf Qaisar met me in his studio in a dingy, dark building in Saddar, claiming that the sealed off spooky rooms had previously housed torture chambers for the MQM. The building, known as Taj Complex, had a dhaba on its ground floor and according to Sharaf, the genesis of Urdu rap occurred at this dhaba over many hangouts of chai and cigarettes. When asked about it today, Talha laughs as he recalls that era. “Back then, and even now, there were no places for live music… especially for young artists, where they can get together and do something. So for us that happened to be Taj Complex."

Having started off at talent shows in school, Talha Anjum and his longtime bandmate Talhah Younus hit instant virality with two songs - Maila Majnu and Burger-e-Karachi. As Talha puts it, “this was the bluetooth era, not even the social media one” in terms of how fans would share music by connecting devices on Bluetooth. But what’s been truly impressive about Young Stunners - as the duo would eventually call themselves - is that unlike many other viral musicians and influencers who were happy to milk their 15-minutes for as long they could, the two Talhas wanted more. “At that point, people might have felt we had made it, but we still thought ‘yeh kya scene hai boss’ - where is this going?”

The young men instead threw themselves into doing live shows and small events, which sounds quite generic and predictable until you realise that this was an era where Pakistan was wracked with terrorist violence, and just stepping out of the house was a risk, let alone holding and performing musical shows. On top of that, the few musical events that did exist usually abhorred rap music, which was little more than a novelty back then. But with some incredible perseverance, Young Stunners kept finding and performing gigs at colleges, private events and more. And all of this relentless performing was augmenting their totally unprecedented rise in the music scene.

Zeerak Ahmed, who helps run the excellent Pakistan-music newsletter Hamnawa, says that “the early-2000s generation of artists were the first to utilize the internet to get popularity. Peer-to-peer sharing (Napster etc) and nascent websites got them early distribution, but they really made it big through TV, sponsorship and live shows. The next generation was drowned by internet bans. Anjum is the only one that survived through those bans in the 2010s, and built an entire career that rests on YouTube. Few, if anyone, have done that at this level."

Zeerak pithily summarises a Sisyphean phenomenon that has defined urban, mainstream music in Pakistan for the last four decades or so. A new technology arrives and almost immediately, tons of new music starts being released. A few years later, that technology changes and almost immediately, a music scene with no copyright system or steady royalties immediately craters. We saw this in the 90s, where the rise began with a new TV channel and ended when illegal cable TV and a pop-music ban on PTV came into play. It was repeated in the 00s, when new music channels led to a rise before a resounding switch to news media and deteriorating social order led to a collapse.

The current era, which forever remains hostage to the threat of internet bans, truly kicked off around 2019-2020, as Youtube and Spotify developed significant audiences. With them came real money made directly off music instead of sponsors. We also saw real data - instead of measuring an artist’s popularity by how many brands they landed, we could now just see actual playcounts. And with that came real reach, as people could finally see that the dinosaur musicians propped up by brand endorsements couldn’t even imagine getting the numbers and impact new artists like Talha Anjum were pulling. And with all of these things in play, for the first time since arguably the collapse of the film industry in the 80s, Pakistan saw a (limited and cautious) return of international music labels, with Talha’s deal cementing this new era for music.

“One thing I've realised,” Talha muses, “is that… my fans are kattar (hardcore) fans,” mentioning the near stampede at his premiere as an example of this intense devotion. For those following Pakistani music, it's hard to recall any other musician with such a huge following. So the question inevitably becomes - why is Talha so popular?

For one, there is the artistry of his lyrics. Over the past year, I’ve come across multiple people telling me that they or someone they knew seriously got into Urdu poetry, or taught themselves the language, after getting into Talha’s music, whose lyrics are often peppered with verses and references from Urdu shayari. For some, he is as much a poet as he is a rapper.

“I do understand my influence in introducing people to poetry…but if people just read a few books, they will develop that interest themselves, much like it happened for me.” Given Talha’s propensity to flex in his song, it was a bit surprising to see his reluctance to take credit. When asked about Jaun Alia, a poet who features frequently in his verses, he reveals that he got into the poet relatively late in life. “The shayari they teach you at school is controlled shayari. I was never really inspired by it, which I think is also due to how we were taught shayari.” Instead Talha discovered Jaun from a Youtube video of the late poet’s mushaira. “He was very different - he was lighting cigarettes on stage and was a whole vibe. And then there is his poetry itself, which feels very new age, very contemporary."

It was in this frank telling that one could see the core appeal of Talha’s persona - his authenticity, a quality which is central to the whole genre of hip-hop. Most of 2024’s rap scene was defined by the epic battle between rappers Drake and Kendrick Lamar, and authenticity lay at the heart of Kendrick’s critique of his rival. There is an expectation that rappers must learn and acknowledge the genre’s past and its uniqueness.

Without meaning to, Talha’s interview gave proof of his own considerable knowledge. He mentions Tupac’s Life Goes On as an example of a music video where the rapper was acting out a character, which inspired his own turn as a thespian in his videos. He references Eminem’s earlier career when I ask him about the challenges of balancing machismo with vulnerability, as Talha has successfully done. When I bring up the age-old refrain that hip-hop has too much gaali-galooch, he references the broader rap culture and its unsanitised ethos. “It’s about culture vs values. I’m not saying that our values are to curse in songs, lekin boss, culture yeh hi hai.”

This deep engagement with hip-hop feels like the basis of Talha’s authenticity, and it is further emphasised when asked about the idea of rap beefs, or feuds between rappers. Are they a strategic means of grabbing attention, or do they reflect the very competitive and instinctive nature of the genre? “There are many rappers who depend on beef to exist, and for them beefing is a science. What I’ve mostly done, there is no science to it. If there’s something I feel the need to address I do it. For me, it’s more of an art.”

What stands out in all this is Talha Anjum’s insistence and ease at being his own self, which is why when he speaks about his future plans, it doesn’t sound like bombast. “I want any rap music that is going on in Karachi - if it is good rap music. I would love for it to happen under my umbrella, under my name. I think I have enough experience that I know how to take that forward. I mean, if I can do it for myself, I can do it for anybody as long as they deserve it. So that is my plan, to make sure that music is released consistently. Because that’s how I did it - I never had any labels or support, all I had was consistency.”

Ultimately, that is probably what has driven Talha Anjum’s unprecedented journey to the top. For all the bling, the huge audiences, the shoutouts from celebrities and the acclaim from across the world, Talha remains defined by a consistent, relentless dedication to his music. Hadi Ahmed estimated that he’s released over 80 songs in the past two years (a number Talha himself struggled to remember when we spoke) and almost each one has been played in the millions.

When asked about what caused him to be prolific, his answer was quite simple. “I feel like I'm in my element when I'm writing or recording, or when I’m working. In those moments, I feel like I’m not just some guy, those moments are something else altogether. ”

For a decade, Pakistani music was caught between struggling to survive, or existing as an extension of marketing campaigns for consumer goods. It took a genuinely authentic, scarily relentless artist with an intimate understanding of his audience to finally break through and create a different future, a different possibility. Today, when someone asks “kaun Talha”, the answer is the biggest, most influential musician in Pakistan right now.